Dr. Melita H. Sunjic

Lecture held at conference “The Future of the Kurds” on 10 October 2018

at the University of Sulaymaniyah, Northern Iraq

The backbone that provides stability and prosperity for any society is its middle class. They have the intellectual capacities and the financial reserves to overcome crises and push an entire national towards a better future. A nation without a middle class has no potential to advance.

In a number of regions in the Middle East and Africa we currently see an exodus of middle-class youth who do not believe that their own country can offer them a life adequate to their skills and ambitions. Northern Iraq is one such region. When young people leave, it is usually the best educated and most dynamic and ambitious segment of their generation. Their loss has a detrimental effect on the future. The society is haemorrhaging its future intellectual, political and economic elite.

What is even more tragic, is that these young talents are losing out as well. If they survive the dangerous journey to Europe, the do not end up in the paradise they expected. Their chance of getting legal status are small. In the worst case, they might be sent back home, after years of trying and losing their best years. If they are allowed to stay, the vast majority will do menial, badly paid jobs, that no European wants. Those who have left their home country in search of careers, happiness and wealth will end up defeated and without either. Sensitisation of the youth about the real consequences of migration is a matter of survival for any nation, including the Kurdish.

Kurds – Statistically invisible

Even though this article attempts to shed light on migratory movements of Kurdish people to Europe, we will not be able to provide exact figures but will use circumstantial evidence. Data available make it impossible to distinguish between Kurds and other nationalities in the region at any stage of the journey.

- Prior to departure: Smugglers cater to language groups. As Kurds usually speak Arabic or Farsi in addition to Kurdish languages, they are able to contract the services of different smuggling networks and it is impossible to quantify how many of the potential clients are ethnic Kurds.

- En route: Migration studies look at migratory flows along geographic routes and provide summary figures. As Kurds migrate together with other ethnic groups they are not discernible as a separate entity and it is not possible to disaggregate the data.

- Upon arrival: Asylum statistics in Europe register citizenship only. Thus, Kurds do not represent a statistical category and are registered as Iraqis, Iranians, Turks etc. and blend in.

For these reasons, the article describes facts and trends, but not exact figures.

Part I — Departure and Journey

The latter is the most relevant for persons originating from the Middle East as well as Afghanistan. Moving in an irregular manner across international borders is obviously illegal and dangerous. This is why people use the services of smugglers which are easily available at all stages of the trip.

Though illegal, people smuggling is a voluntary transaction between consenting parties, a service provider and a client. (It should not be confused with “trafficking in humans”. Trafficking involves deceit, coercion and exploitation. The person is trafficked against his/her will.)

The smuggling business is demand-driven and profitable and – according to Europol – the fastest growing branch of international organized crime. In regions where the need arises, transnational criminal networks move in quickly. It is often (former) drug and arms dealer rings which “diversify” their business and start transporting people. For the smugglers, it is by far less dangerous to transport people across borders compared to running arms or drugs. Moreover, it is socially less stigmatised – at least in countries of origin and transit.

The modus operandi of smugglers

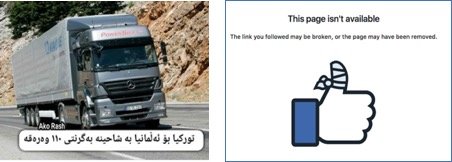

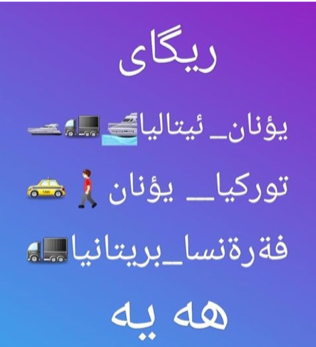

Providers and clients get in touch through direct interaction at popular departure points or via Social Media. Offers on Social Media are in Dari/Farsi, Arabic and – increasingly – in Sorani. Sorani speaking smugglers use mainly Facebook to reach the community, Instagram being not so common for the time being. There are dozens of active Sorani Facebook accounts. Each smuggler has over 4,000 friends and each post generates numerous reactions.

On their advertisements, smugglers use visual signs, audio messages, Google Earth, Google Maps, flags of EU countries, and photos of important personalities (for instance Angela Merkel’s photo as Facebook Background images) and they post success stories of people they have transported.

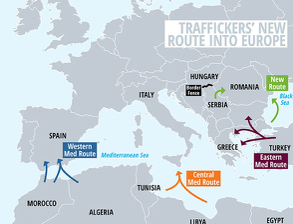

Sorani speaking smugglers promote trips from Erbil to Turkey as well as onward trips from Turkey to Italy, Greece, Germany, France and the UK. They use Bulgaria, Romania, and Hungary as transit countries. In August/September 2017, they widely promoted trips via the Black Sea from Turkey to Romania and then to Germany by truck which is a relatively new route.

The prices of Sorani speaking smugglers are slightly higher than those of Farsi and Arabic speaking smugglers, and they prefer US-Dollars to Euro. For example: In August 2018 the average price of a boat trip from Turkey to Italy was EUR 2,700 on offers in Farsi, EUR 6,000 in Arabic offers and USD 7,500 by a Sorani speaking smuggler.

Apparently, the smuggling business is largely unencumbered by border controls, as several smugglers are able to offer regular weekly trips between Northern Iraq and Turkey for USD 900.

At the beginning of August, a smuggler account presented the entire journey from Turkey to Hungary via Bulgaria and Romania on Google Maps. There were photos of the cities and distances to cross, the location of bus stops at each border where potential migrants and smugglers meet as well as means of public transport such as buses, trains and taxis. This page has been closed down in the past weeks.

More evidence of the activities of international networks is provided by the fact that smugglers also sell fake and stolen ID documents on Social Media and must have access to corrupt officials in embassies as they can provide visas for multiple countries.

This is a Facebook post in Sorani language as of end August 2018 offering French visa for EUR 12,000

Recently, numerous closures of smuggler accounts have been observed, possibly due to a crackdown by law enforcement agencies. This might also be why we see a rise in the number of accounts in Sorani. Many law enforcement agencies use computer translation programs when searching smuggler pages. However, Sorani is not part of Google Translate and cannot be detected unless the agency employs Sorani speakers.

Refugee or Migrant?

Smugglers could not conduct their business if there was no demand for irregular migration and if there were no people trying to get Europe in search of a better life. More often than not they are unaware of the crucial legal distinction between refugees and migrants until they arrive in Europe and lodge an asylum claim.

A refugee is person who has been forced to flee his or her country because of a well-founded fear of persecution for reasons of race, religion, nationality, political opinion or membership in a particular social group. The most common causes for flight are political, ethnic, tribal or religious violence. The refugee definition is stipulated in the 1951 Geneva Convention and legally binding for all signatory states. One of the most fundamental principles laid down in international law is that refugees must not be expelled or returned to situations where their life and freedom would be under threat. When they lodge an asylum claim they will receive international protection, be it asylum or humanitarian status.

Migrants are persons who take a voluntary decision to leave home in search of economic security, education and better opportunities or for family reasons. Unlike refugees, migrants are not under a direct threat of persecution or death in their home country and can therefore can sent back. In view of increasingly restrictive migration policy in Europe, migrants who arrive by irregular routes will most likely not get the chance to stay or obtain legal residence. So they run a high risk of being deported home and lose all the money they invested to get to Europe.

Part II — Situation upon Arrival[4]

Most people who set out for Europe are aware that the trip might be dangerous, but they think it is worth it. Experience shows that there are many more dangers than expected and that in many cases the suffering and the financial loss is not rewarded by a good life in Europe or the opportunity to take care of families back home. The situation differs from one transit country to another.

Turkey

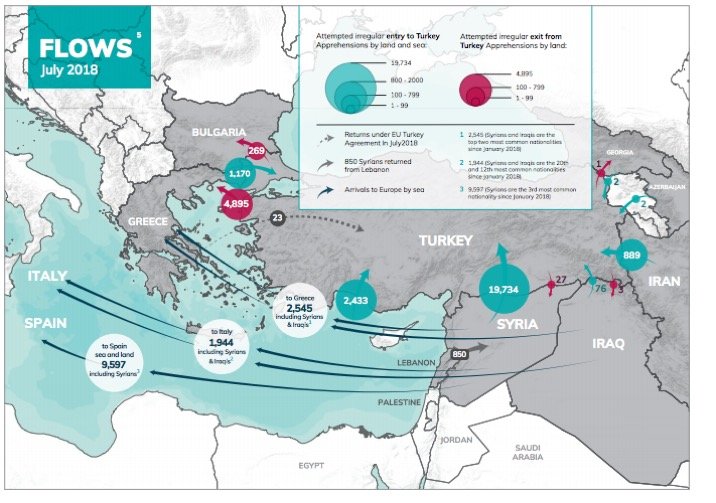

Turkey is the last transit country before Europe. There are reports of police violence, detention, fines that had to be paid. People get stuck for many months because they have to work to pay for onwards smuggling. Some individuals are intercepted at land and sea borders and brought back to Turkey. A small number or people is returned from Greece to Turkey under the EU-Turkey agreement[5].(390 Syrians and 63 Iraqis between April 2016 and August 2018)

At sea, 99 died in 5 incidents in the first semester of 2018 which is twice as many as in 2017. On land routes, at least 17 people drowned in the Evros River between Turkey and Greece, including young children. An additional 13 persons were killed in car and train accidents.

En route to Greece, at least 140 persons reported incidents of sexual abuse in the first semester of 2018, but it is safe to assume that many more incidents go unreported due to a reluctance of irregular migrants to get in touch with authorities.

Greece

As of July 2018, 61,000 asylum-seekers were staying in Greece, roughly 16,000 on the islands and 45,000 on the mainland. 40% of the asylum seekers in Greece are men, 24% women and 36% children (600 of them travelling without an adult).

26,000 new arrivals were registered between January and June. Of those, 16,000 came by sea and 10,000 by land. 35.3% came from Syria and 21.2% Iraq. There is no way to know how many of them are Kurds. Reception and Identification Centres in Greece are seriously overcrowded, housing three times their capacity and the situation is worsening. There is shortage of staff, hygienic conditions are abominable, and riots and violence among refugees is a common occurrence.

UNHCR only has accommodation for one third of the people (21,000 apartment places in 22 cities). Some vulnerable individuals receive cash assistance. Many migrants and refugees are homeless, including families and unaccompanied minors.

The EU has a plan to relocate asylum seekers from Greece to other Member States, but the process is slower than the rate of new arrivals. In the first half of 2018, 22,000 people left Greece while 26.000 new arrivals were registered.

Balkans

Crossing the Balkans is long and difficult. Many borders are tightly controlled or closed off by fences. So people keep listening to rumours about openings here and there and move back and forth between different countries.

On the Balkans Route, the scale of abuses by smugglers is lower than in the Central Mediterranean, but they exist nonetheless. There are reports of migrants being held captive to extort more money, being left without food and water. Robberies by local gangs have been observed as well.

At least 26 people were killed in 22 separate incidents while travelling irregularly through the Balkans. Of these, 12 drowned, most of them at the Croatian-Slovenian border.

Push backs are recorded from Bulgaria, Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, FYROM, Hungary, Montenegro, Romania, Serbia and Slovenia. People are denied access so asylum procedures. Sometimes they are even forcibly sent to countries they have not been in previously (e.g. from Croatia to Serbia).

Serbia

Irregular migrants on average spend 18 months in Serbia while trying to find a way forward into an EU country. Just under 4,000 are officially registered and assisted, but no one knows the actual number.

Hungary

Hungary is completely closed off by a fence with two transit zones left where asylum-seekers can submit their claim. Fewer and fewer persons are admitted each week. Currently, 10 persons per week are allowed to enter. Once in Hungary, they are automatically detained. New legislation restricts assistance to refugees by NGOs or private individuals.

People trying to cross the fence are immediately turned back to Serbia (19,000 in the first semester of 2018). Those who make it into Hungary illegally are not given access to the asylum procedure when intercepted but detained and also returned to Serbia (280 persons in 2018).

Bosnia and Herzegovina

Over 10,000 arrivals have been recorded Bosnia and Herzegovina by end July. The government has reception capacities for no more than 400 people. The rest live in hard conditions in improvised tented camps and dilapidated buildings or in the streets.

Old EU Member States

Migrants who pass the ordeal of the Balkans route and make it to Central Europe and onward, only to find out what the smugglers did not tell them. They often are surprised that they are not allowed to choose their destination country but have to stay where their fingerprints were first registered (Dublin II Regulation). If they leave on their own, they will be sent back forcibly. And even iv they manage to get to the country of their dreams, they will soon see that they are not welcome.

Mass accommodation and no access to jobs

Asylum-seekers are placed in crowded mass accommodation centres, often in remote areas, where they receive only basic food, primary health care and primary education. In several European countries their movement is restricted to certain districts. They usually do not get cash assistance but very little pocket money at best.

In most countries, asylum-seekers have to wait up to two years for the first asylum interview, and it may take many more years until they obtain a final decision about their future status. So they live in limbo for a long time, not knowing if they will have the right to stay or be sent back. Access to employment and higher education is restricted during that time in most countries.

Recognised refugees struggle with integration

Some do make it. In the EU+ region (including Norway and Switzerland) 94% of Syrian citizens and 56% of Iraqi citizens obtained asylum or humanitarian status in 2017.

Then integration starts in earnest. Refugees need to leave their reception centre and find a place to live on a continent where affordable accommodation is scarce. Moreover, many landlords do not want to rent out to refugees.

When looking for jobs, they discover that they cannot get a job in their previous field of work without language skills and diplomas recognized in the EU. Often, computer skills are required even for blue collar jobs.

Many refugees are not aware that will not be allowed to travel to their country of origin with their refugee travel documents or they will immediately lose their protection status. So, going home for Eid or visiting the family for marriages or funerals is out of the question.

Adaptation to the new societies reaches very personal levels: Family structures change. Children will want to behave differently from home. They want to dress as they like, go out with friends of both genders, even smoke and drink. Wives will also change their attitude and demand more freedom for themselves and support in the household. The number of refugee wives filing for divorce in Europe is increasing and has become a constant topic of discussion on Social Media. No wonder that some people decide to return.

Voluntary and forced returns

Not all returns are voluntary, and EU Member States are stepping up their efforts to forcibly return rejected asylum seekers. Such return pogrammes also involve Kurds from Iraq. In 2016, at least 26 Kurdish asylum-seekers have been deported from Britain and – at the time – over 70 more were imprisoned awaiting return. [9]

In February 2018, the German authorities expressed their hope of repatriating 10,000 Iraqi refugees to Iraq through the establishment of migration advisory centres in the Kurdistan Region and in Baghdad.[10]

Part III – EU Internal & External Refugee Policy

Since 2015, when a million asylum-seekers arrived in Europe, the attitude towards migrants and asylum-seekers in the European population as well as the responses of governments to the influx have become increasingly negative. The 27 EU Member States have proved incapable of finding a common solution. Instead, each government is driving its national policy which in most cases aims at shifting responsibilities for those who are already in Europe and closing the borders and externalizing asylum for those who wish to come. The growing influence of far-right parties in complicity with tabloid media have created a feeling of panic about a seemingly unmanageable onslaught of refugees.

A soberer assessment of the data reveals that the problem is mainly one of distribution and management within the EU. In absolute numbers, Germany, Italy and France host the most refugees. Per capita, Greece and Cyprus are on top of the list with over 5,000 per 1 million inhabitants. This is still by far lower than in countries such as Jordan with 173,000 or Lebanon with 89,000 refugees per 1 million inhabitants.[11]

In all, a minority of countries, at the EU external borders as well as Germany, Sweden and Austria are processing the vast majority asylum claims and there is no consensus on responsibility sharing. In fact, the countries that have the fewest asylum-seekers and refugees, the so called Visegrad Group, are the ones most afraid of new arrivals, and they are vigorously pushing an anti-refugee agenda in the EU. The V4 is composed Slovakia (27 asylum-seekers per 1 million citizens), Poland (79 / 1 million) Czech Republic (108 / 1 million) Hungary (318 / 1 million). Their strategy is echoed by Austria, Italy and the German Federal State of Bavaria who all have far right parties in the governments. [12]

No common asylum standards

Since 1999 the EU has been working on the creation of a Common European Asylum System. What has been achieved until 2015 is now rapidly falling apart.

Below is a selection of headlines illustrating the developments of a recent weeks only. This information was collected by the Asylum Information Data base (AIDA) which is managed by the European Council on Refugees and Exiles[13]

-

- Portugal: Persisting Detention of Children at the Airport (4 September 2018)

- Germany: Measures Restricting “Church Asylum” Contradict Case Law (31 August 2018)

- Austria: Plans to Abolish Asylum Seeker Apprenticeships (30 August 2018)

- Hungary: Asylum Seekers denied Food Following Inadmissibility Decisions (17 August 2018)

- Italy: Ministry Circular Urges Restriction of Humanitarian Protection Status (11 July 2018)

Panic in Europe

What caused this panic in Europe? There are many reasons, but cultural fears are on top.

Egged on by right wing parties and tabloid media, Europeans are afraid of losing their identity to newcomers who have different ways of living, speaking and dressing, different views on democracy, religion, morals and gender roles and who have a tendency of creating segregated ethnic and cultural bubbles. The European working class is afraid that all these newcomers are burdening the social system, including education and health care and are they are competing with them on the labour market.

Also, there have been incidents of large and small-scale Islamist terrorism which scare the population. Consequently, any transgression or crime committed by a migrant or refugee is blown out of proportion by tabloids and right-wing politicians, reinforcing resentment. In addition, public discourse does not distinguish between irregular migrants and real refugees, between honest people and criminals, but stigmatizes all foreigners.

Preventing access to EU territory

As a consequence, many European governments are rallying to tighten the external borders to prevent irregular migrants from accessing EU territory. Recently, there are more and more calls by European politicians for reducing or even stopping rescue operations at sea.

Several Member states such as Greece, Bulgaria, Hungary and Austria built fences at their southern borders. The European Union is massively reinforcing its common external border controls. The European Border and Coast Guard Agency Frontex plans to triple its budget und boost its personnel by a factor of 10 in the coming years.

In some cases, Kurds are directly affected by access restrictions. In April 2018, Greece started fearing a massive influx of Kurds fleeing Syria and, in collaboration with Frontex, took preventive measures to restrict their entry.

New arrivals trying to enter Greece[15]

Europe is surrounded by numerous crises from which people are fleeing: North Africa, Sudan, Somalia, Eritrea, the Middle East, Afghanistan. Most people do not flee to Europe right away but try to stay close. Only when the countries of first asylum are overwhelmed they move on. In case of the war in Syria it took from 2011 to 2015 until refugees started coming to Europe.

In addition, there are people who just want to work in Europe for a while, make some money and go back home, as they previously did in Libya. Europe, though in need of work force, does not have a functioning labour migration strategy which is why all new arrivals – refugees and economic migrants alike – are using the asylum avenue to get it in, clogging and overwhelming the system.

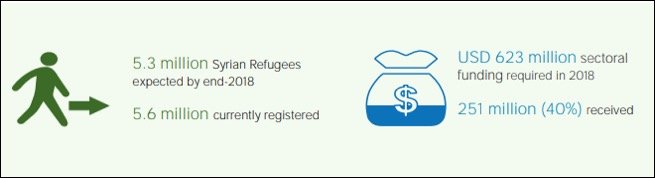

So, if the EU does not want refugees to move on to their territory, the logical step would be to help them in the crisis region, by supporting the neighbouring countries. That would be cheaper for Europe and less dangerous for the refugees. But it is not happening. As of early September 2018, the UN inter-agency Syrian Regional Response Plan was underfunded by 60%.[16]:

These days, this concept is in the cards again. On 28 June 2018, the European Council endorsed the plan for “regional disembarkation platforms”, meaning that migrants rescued at sea would not automatically be brought to EU territory but to a centre in a non-EU country, preferably in North Africa where their asylum claims would be processed.

There is a major practical obstacle though: No state outside the EU is prepared to open such a centre on its territory. The alternative, processing centres on EU soil, has been tried already in Greece and has not been working so far as discussed earlier in this text.

So, what is the conclusion? Refugees and migrant keep trying to get to Europe. In the absence of a comprehensive strategy to deal with irregular migration the EU is somewhat randomly taking steps for barring irregular entry. Many migrants are losing their lives or at least their money and hopes on the way to a good life in Europe. The only ones constantly benefitting from this development are international criminal smuggling networks making “a killing” both in the figurative and literal sense of the phrase.

[1]Belinda Robinson ‘Mapped: The new back door route migrants are taking to reach Europe’, Daily Express, 18 August 2017. Available at https://www.express.co.uk/news/world/841925/migrants-EU-back-door-smugglers-people-traffickers-black-sea-new-route (accessed: 6 September 2018)

[2]Mixed Migration Centre, ‘Monthly Trend Analysis MMC Middle East & Eastern Mediterranean’, July 2018. Available at http://www.mixedmigration.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/MTA-me-1807.pdf (accessed 6 September 2018)

[3] This and the following images in Part II are screenshots taken from smuggler pages on Facebook in Sorani language and dating from August 2016. Some of them are no longer online at the time of writing. For security reasons the sources cannot be revealed.

[4] All figures for this chapter cover the period from January to July 2018 if not indicated otherwise. Source: UNHCR Operational Portal Refugee Situations, Available at: https://data2.unhcr.org/en/situations (accessed 6 September 2018)

[5] Official Journal of the European Union, ‘Agreement between the European Union and the Republic of Turkey on the readmission of persons residing without authorisation’, March 2016. Available at https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex:22014A0507(01) (accessed 6 September 2018)

[6]UNHCR, ‘Desperate Journey January 2017 – March 2018’, March 2018. Available at https://data2.unhcr.org/en/documents/download/63039 (accessed 11 September 2018)

[7] Kian Ramezani, ‚Iraker sind auf der Flucht aus Europa zurück in den Irak‘, Watson, 12 February 2016. Available at: https://www.watson.ch/schweiz/international/767074514-iraker-sind-auf-der-flucht-aus-europa-zur-ck-in-den-irak (accessed 8 September 2018)

[8] Heidi Huber: ‚Ticket ohne Rückflug – Irakischer Flüchtling verläßt Salzburg‘, Salzburger Nachrichten, 1 February 2016. Available at http://www.sn.at/salzburg/chronik/ticket-ohne-rueckflug-irakischer-fluechtling-verlaesst-salzburg-1777510 (accessed 6 September 2018)

[9] Rudaw Media Network, ‘Britain deports 26 Kurdish asylum seekers, imprisons 70: monitor’ 29 March 2018. Available at http://www.rudaw.net/english/world/290320181 (accessed 8 September 2018)

[10] Nadia Riva, ‘Germany to repatriate thousands of Iraqis to Kurdistan, Baghdad’, Kurdistan 24, 29 March 2018. Available at http://www.kurdistan24.net/en/news/058c2408-dd80-48c0-b7af-d08fa1185a80 (accessed 8 September 2018)

[11] Niall McCarthy, ‘Lebanon Still Has Hosts The Most Refugees Per Capita By Far’, Forbes, 3 April 2017. Available at https://www.forbes.com/sites/niallmccarthy/2017/04/03/lebanon-still-has-hosts-the-most-refugees-per-capita-by-far-infographic/#4affa8083970 (accessed 9 September 2018)

[12]‘ Das Statistik-Portal, ‘Europäische Union: Anzahl der erstmaligen Asylbewerber je eine Million Einwohner* in den Mitgliedsstaaten im Jahr 2017‘, Statista, 2019. Available at https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/156549/umfrage/asylbewerber-in-europa-2010/ (accessed 17 January 2019)

[13] News and Updates from ADIA and our Partners. Available at http://www.asylumineurope.org/news

[14] BBC News, ‘Europe and nationalism: A country-by-country guide’ [infographic], 10 September 2018. Available at https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-36130006 (accessed 10 September 2018)

[15] Sputnik News, ‘Greece Tightens Border as Kurds Flee Syria Following Turkish Invasion’, Online Photograph, [Marko Djurica, Reuters], 30 April 2018. Available at: https://sputniknews.com/europe/201804301064022394-greece-border-turkey-migrants/ (accessed 7 September 2018)

[16]UNHCR, ‘3RP 2018-19 Regional Refugee and Resilience Plan –Quarterly Update – Achievements’ June 2018. Available at https://data2.unhcr.org/en/documents/download/65425 (accessed 7 September 2018)